Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

It’s already been two weeks since the world leveled up from 2024 to 2025. In another two weeks it will be a year since this blog has gone public with the first post. This will be a brief review of what this site achieved, what it didn’t, and what I hope it will achieve this year.

tl;dr

- More frequent posting of shorter articles in 2025

- Dungeon 24 continues on irregular schedule

- At least 3 new Dungeon series articles planned

- Whole new exciting series coming soon

- Finally some game analyses!

Goals set and met

My goal when I started with this blog was at least one post per week. That changed to two per week with the addition of Dungeon 24. Which should get us at 104 posts total. And that’s not counting various random acts of writing I thought I would be committing.

There are 13 published posts on the site in 2024, far less than I expected. I’ve been quite optimistic, as I thought to have enough topics to cover, which was and still is true. What I didn’t have was the time to write all the longforms I envisioned. I am used to working with sources, citing (or at least checking) everything, polishing the language and revising if needed. When I publish something I want to be able to stand up for my work. The schedule I set for myself was rather unrealistic, as I’ve learned.

Dungeon 24

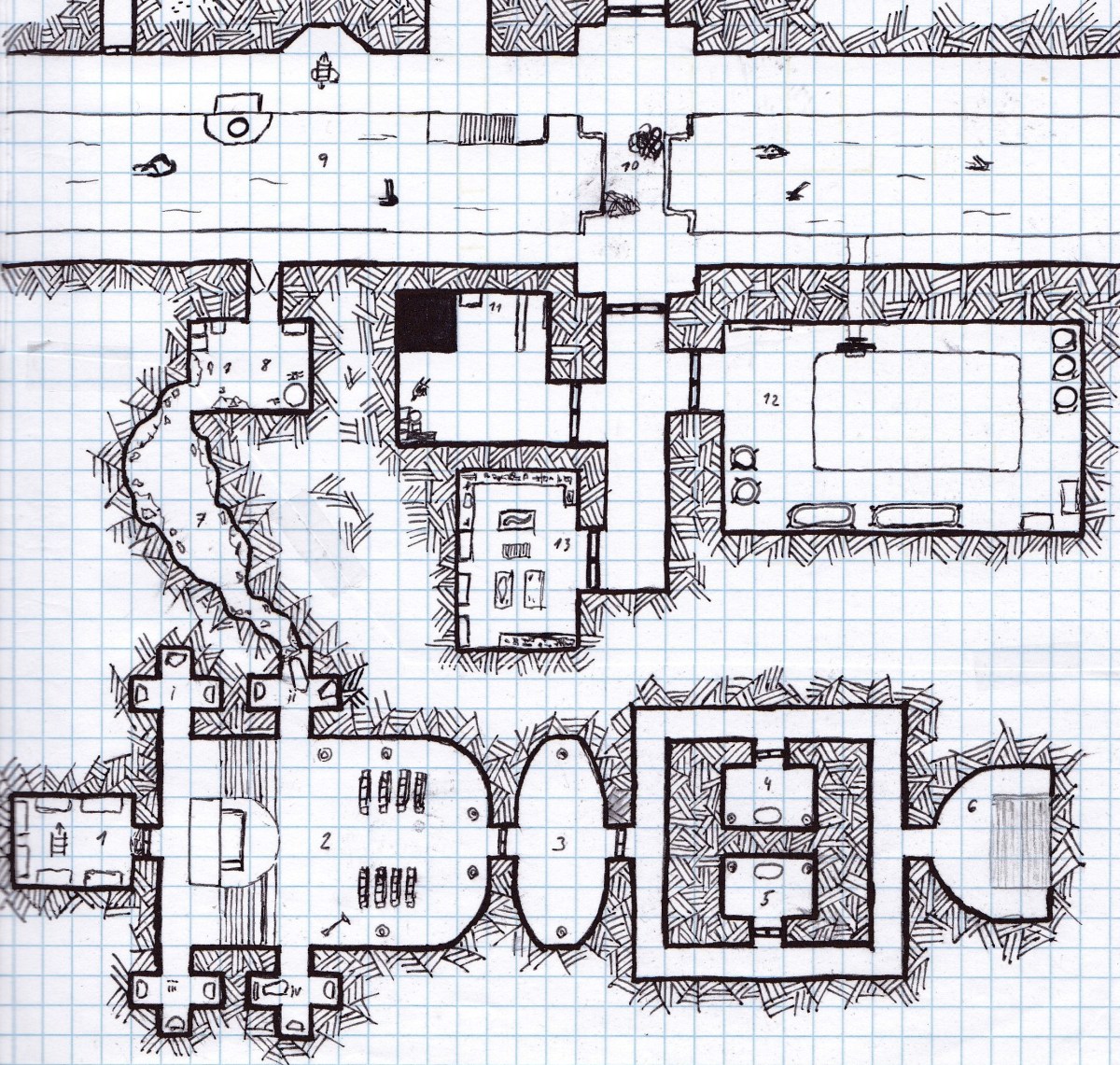

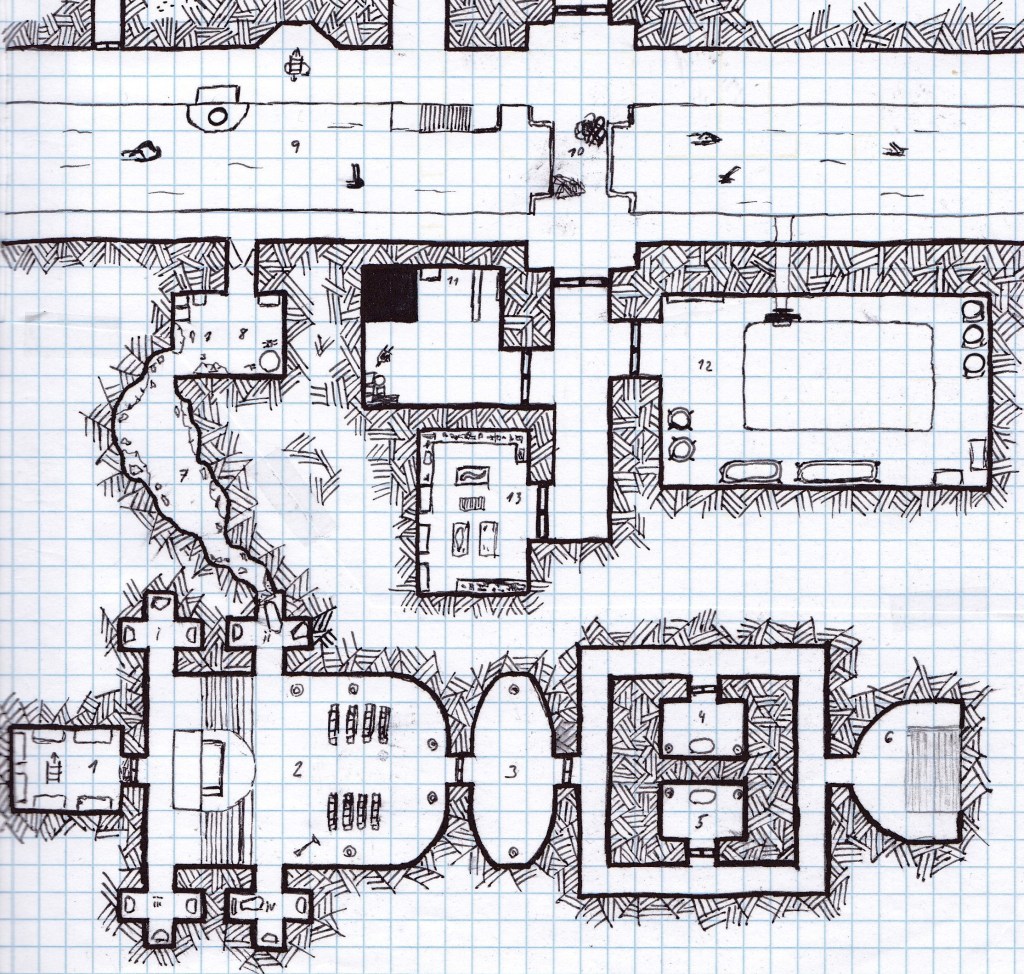

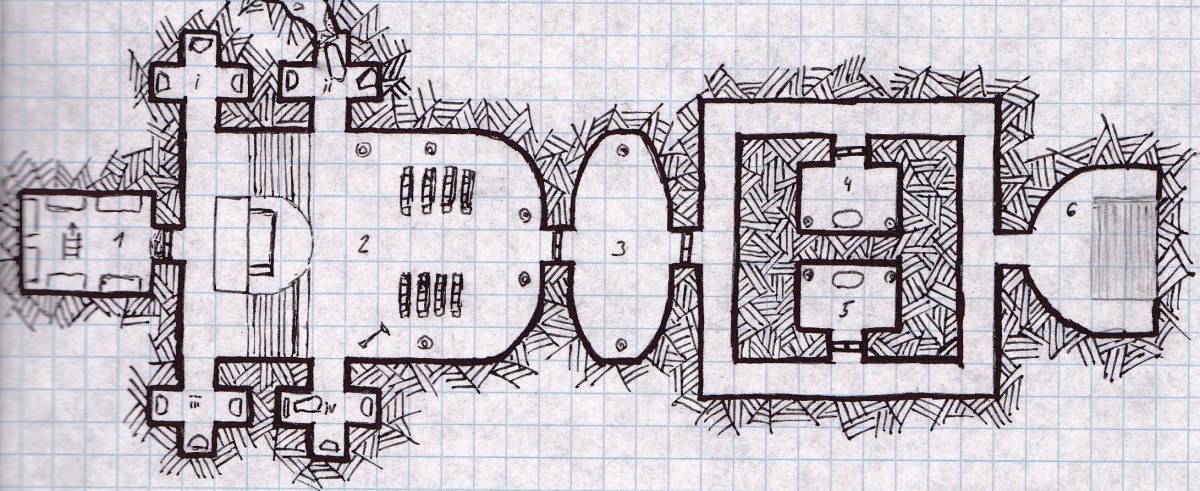

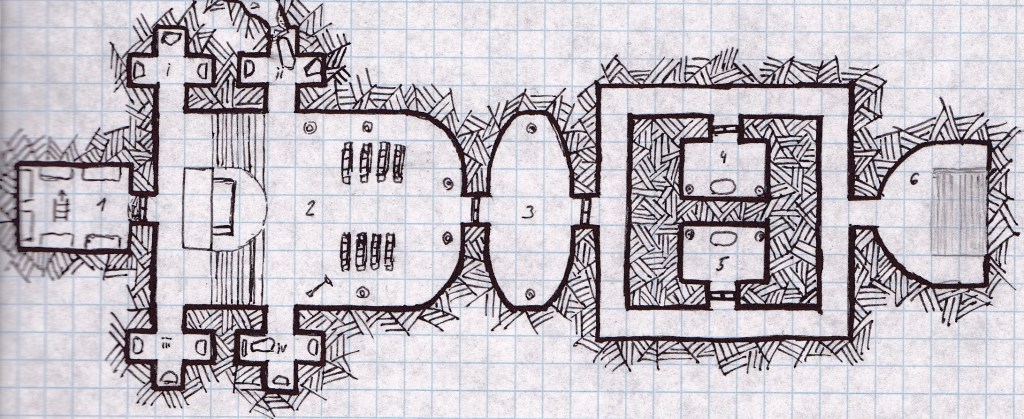

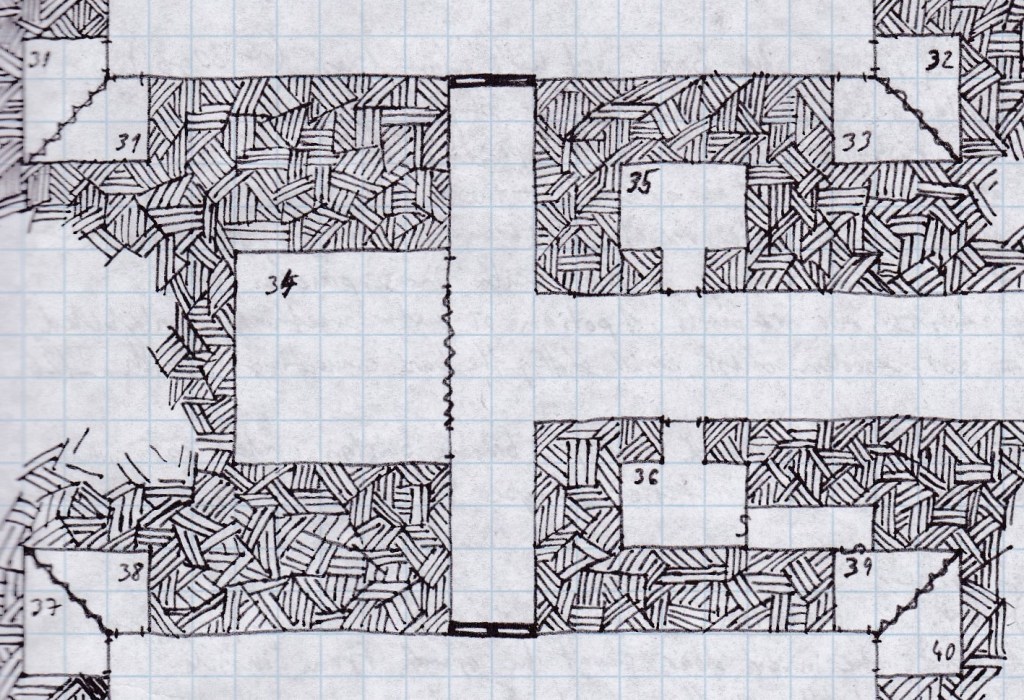

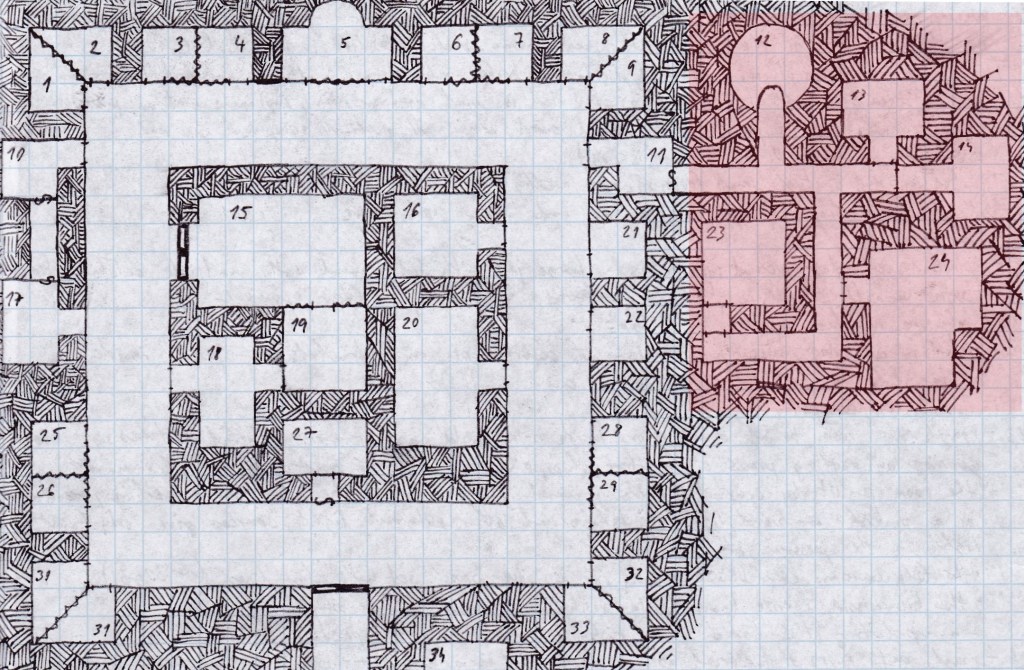

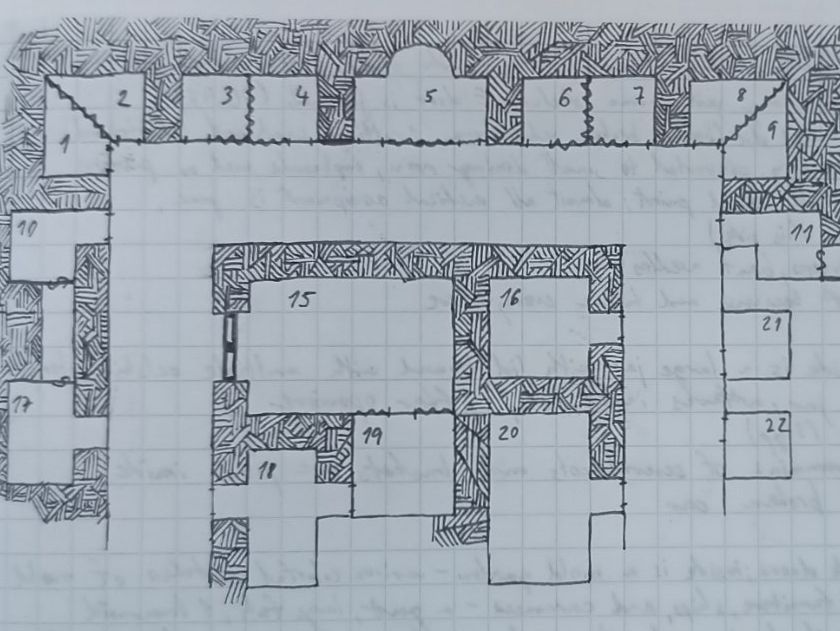

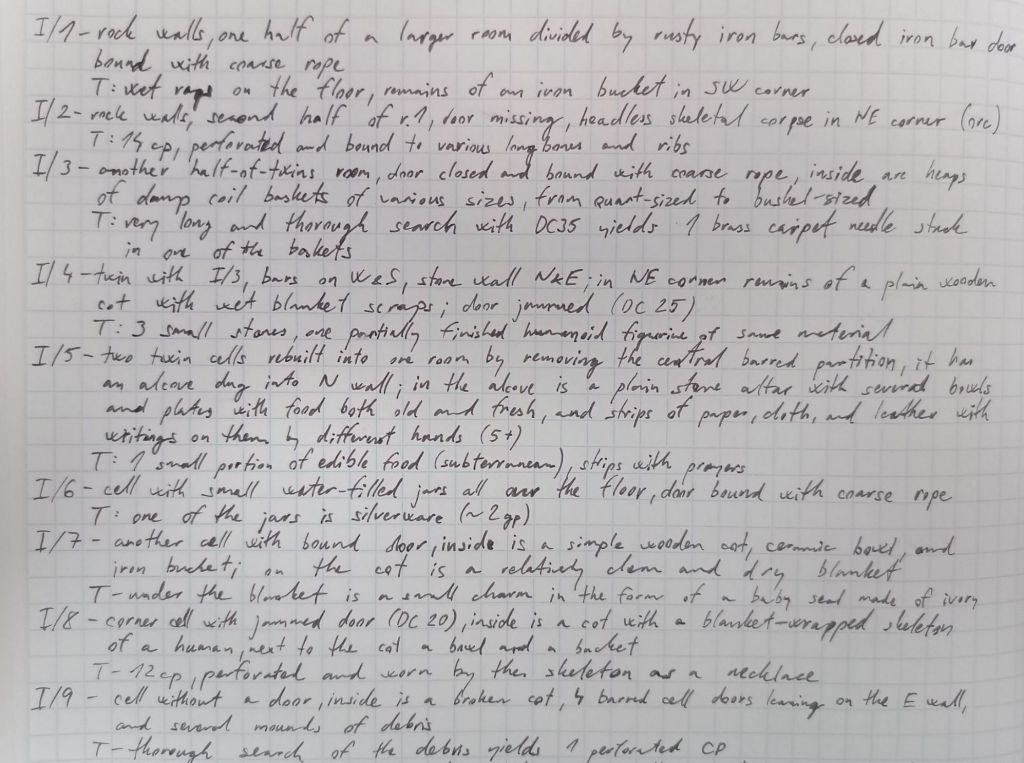

My apparent nemesis, the Dungeon 24 challenge. I stated in the beginning that this type of challenges isn’t really for me, and I was right. I managed for a few weeks but after that I started getting more and more behind the schedule. The last update was in September and it should cover the first half of March. I have more in my notebook, but couldn’t get to processing it for the blog.

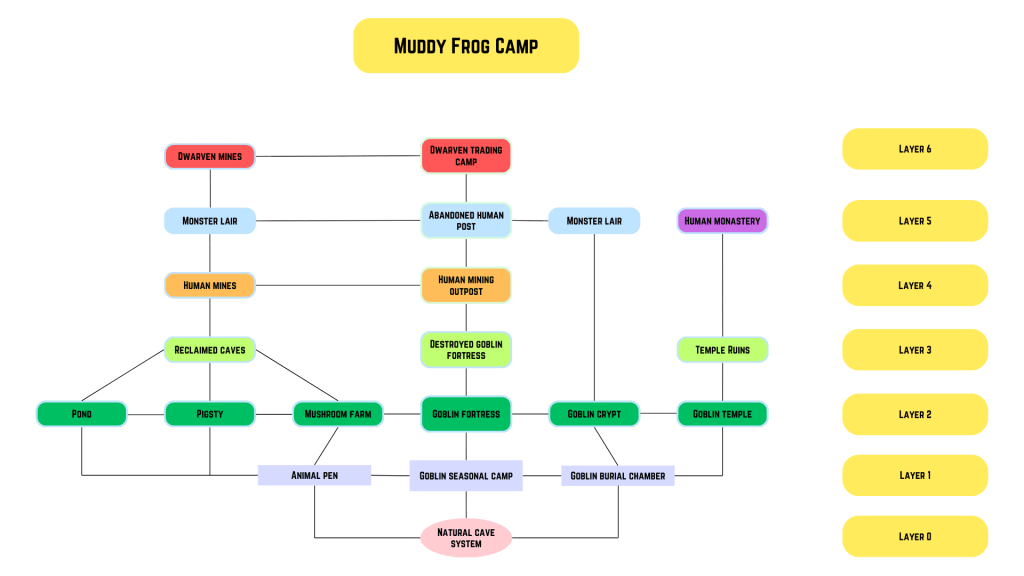

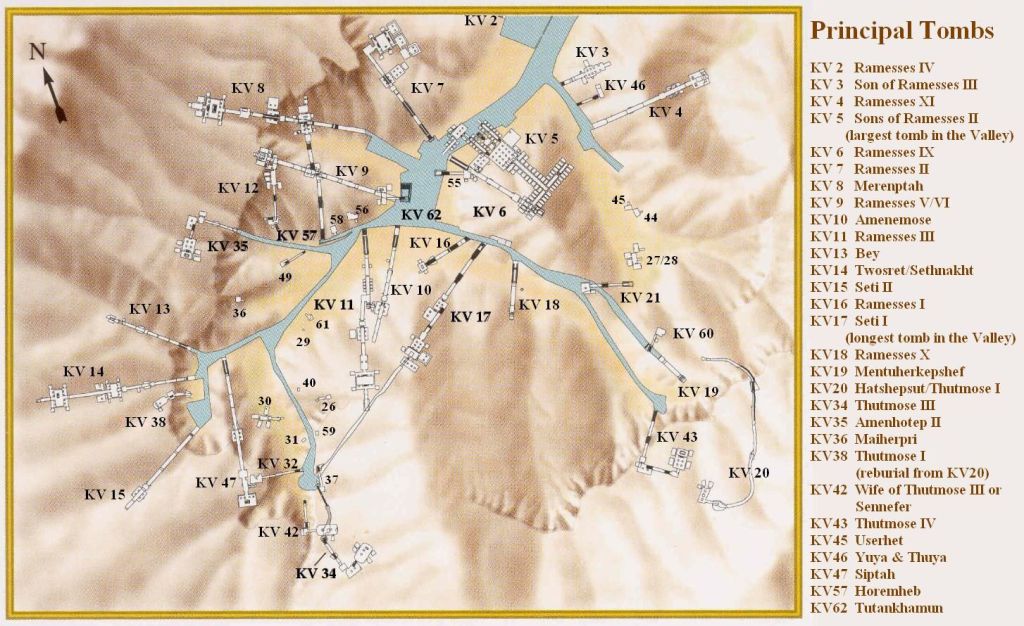

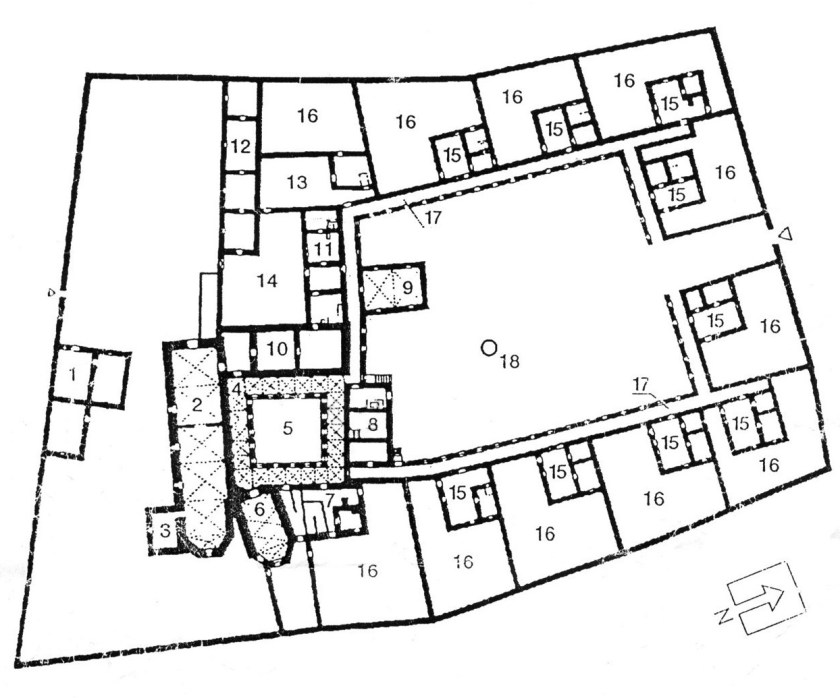

Nevertheless I will continue with the dungeon this year until there are at least 365 rooms. There are still ideas I want to put in there, and I don’t want to leave it unfinished. It also serves as a laboratory and test tube for the Dungeon series of articles on this blog. The frequency of the updates will be irregular, same as with the other article types.

There’s one other thing worth mentioning. The article with the most views in year 2024 was the introductory post to Dungeon 24. Somehow my site is the number 3 result on Google, which is nice, I guess. I would rather have traffic for my other work, but if it helps people get to the site, it’s fine.

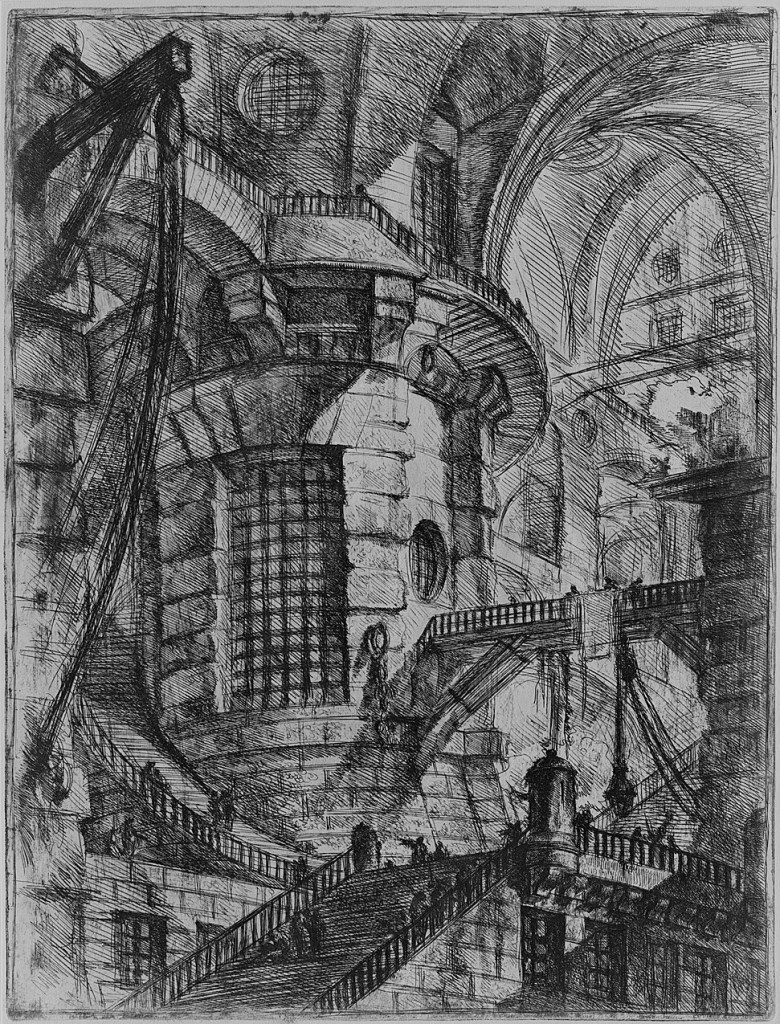

Dungeon series

I consider the Dungeon series the current flagship of the blog. The articles published so far offer my views on different aspects of dungeon design and functioning. In the three published articles I have discussed dungeon size and megadungeons, the way dungeons should and could be explored, and the Palimpsest dungeon concept. Dungeons, in their many forms, are an integral part of TTRPG experience for many, regardless of the system or setting. So far I’ve concentrated on fantasy settings, but many of the ideas presented in the articles should be useful for other types of settings as well. Anything can benefit from solid internal logic instead of theme parks composed of unrelated challenge sequences.

I have two more articles in various states of completion, that should be ready this year. In one I will elaborate on the Palimpsest dungeon concept. The other will deal with bringing life to the dungeon. At least three more exist as outlines on my to do list. These will deal with stuff like level interconnectedness and verticality, if that’s a real word. More topics will surely progressively arise from other activities, including the ill-fated Dungeon 24.

Different topics

Apart from the Dungeon series I managed to write three articles providing summaries of a certain topic. Each deals with a different area – settings, items, and general theory.

In Frozen Horrors I described a setting type notable for combining harsh environmental conditions and isolation with horror themes. I actually wanted to make several updates with more works, but didn’t find the time to do the necessary research. There are still movies, books, and video games that could fall into this sub-genre. Not all are suitable to take inspiration from, but that’s up to the readers of course.

Slingshots part I was a summary of this toy/weapon in various media. I’ve been particularly focused on how slingshots are explained and presented – viable weapon or novelty? Again there are other media that could have made the list, and I’m slowly working on an update. There will also be a Part II sometime this year, although it’s not a priority. It will deal more directly with the application of slingshots in your games and settings. I think an article on slings is in order as well, as a comparison between a real weapon that killed people on the battlefields versus what is a modern improvised weapon at best.

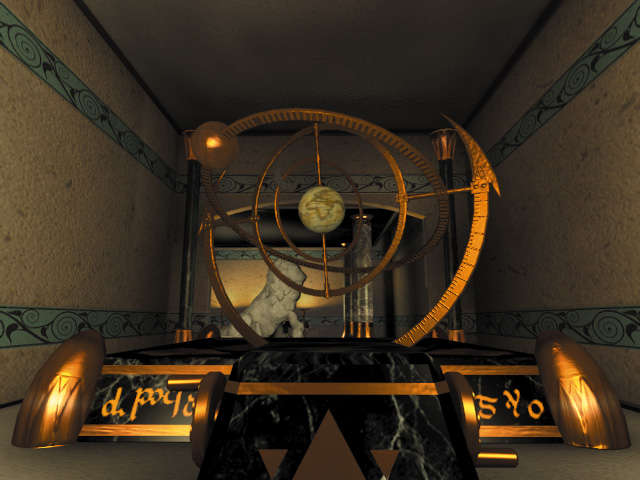

The article on using video games as a resource is a sort of necessary introduction to a type of article I plan on adding to the repertoire. As mentioned in the post itself, these won’t be game reviews as known from gaming blogs and magazines. Things like hardware requirements, controls, or replayability won’t matter as much as storytelling, ideas, and inspiration potential for your tabletop games.

What to expect in 2025

This year there are going to be some changes. There is a lot I still have to learn and fine-tune. So far I focused on longforms that required some research and thought on top of the idea and writing. This led to very sporadic updates. My goal is to be more active, so in addition to these longforms I will be posting shorter posts. Likely true blog posts with various thoughts and ideas that I might elaborate upon in the future.

I haven’t published any playable material, yet. There are several class options for D&D on my table I’d like to see finished, so these will have priority. Some need only cosmetic changes so they come in a nice package. Though it’s the contents, not the form, that matters, I wouldn’t want to publish it as bland text files. Other systems like 2nd edition Pathfinder and Mörk Börg will also receive some attention when possible. Unlike theory, which I believe to be mostly universal, different systems allow different supplements.

The main focus of the blog will remain on theory, as I intended from the beginning. For the longforms the Dungeon series will remain the main theme, so expect more in that vein. I have a few other avenues that I would pursue. Some I have outlined above, such as a follow-up to the article on slingshots. I also want to start another series of articles focused on different materials. Some that are readily available in most settings, some that are rare. I have some possibly controversial takes that might not suit everyone, but I very much look forward to exploring these ideas.

I will try to publish a few of the video game analyses I advertised. So far I haven’t finished any of those, even though I have a few in process. This year I plan on finishing at least some game articles. One hot candidate would be Arco, a fine RPG with a captivating Mesoamerican setting. Do check it out!

Final remarks

It would probably be a good thing to set concrete measurable goals for this year, though I am reluctant to commit to precise numbers. I think that with less focus on longforms and more shorter posts I could get at 30 articles this year. There will be the Dungeon series articles, and a new series that I’m keeping as a surprise until the first article is ready.

I also want to put more effort into promoting the site, so that it gets a little more life. For example the Frozen Horrors article had 3 likes out of only 4 views. This tells me that people find the stuff I write interesting if they find out about it.

With this in mind I would like to ask again to share the articles you like. We all have our networks and your sharing is the best way for the blog to spread. This is the kind of feedback I need to improve the site. That and the comments. Please take a moment to write down one or two sentences about what you liked, or even where you disagree. Having constructive discussions under the posts would be wonderful.

I would like to wish you all a fruitful and satisfying year 2025. May you achieve your goals and have lots of fun with TTRPGs or any other hobbies you have. Also take care of yourselves and your close ones, stay safe through the year!