In case you haven’t heard, Wizards of the Coast have announced in late February that a new sourcebook is in works. It will resurrect the dual plane Lorwyn-Shadowmoor from Magic: The Gathering, released back in 2007-2008. There was the Lorwyn block, comprised of Lorwyn and Morningtide, and the Shadowmoor block, consisting of Shadowmoor proper and Eventide.

I wanted to dedicate a series of articles to MtG with focus on those two blocks, but Wizards beat me to it with their announcement. There’s no release date so far, so I’ll go for it anyway and write my thoughts, expectations and speculations. I am really looking forward to the end product and wish the team behind it luck. Lorwyn-Shadowmoor is a great setting and should not be left to rot.

Lorwyn-Shadowmoor is clearly inspired by British Isle folklore. It shows in the language, themes, and aesthetic, but it was never marketed in this manner. The creators probably wanted to create a setting influenced by folklore and fairy tales, not build a setting around folklore.

In this article, hopefully first of many, I will describe some of the cosmological aspects of Lorwyn-Shadowmoor in regard to Dungeons and Dragons. There are my speculations on the place of the plane in the multiverse(s), and inevitably a quite large part on the timeline. I wanted to get these out of the way before I start writing about more specific topics, such as the various denizens of the plane.

Dual plane

Lorwyn and Shadowmoor are unique in that they’re two sides of one setting. A dual plane changing periodically because of the Great Aurora. Originally a recurring event orchestrated every few centuries by Oona, queen of the fairies.

Many such events have happened apparently, until the last one (the one we see in the MtG blocks). That one was not caused by Oona, to her great unease and discomfort, but rather brought by the Great Mending. The Great Mending is an important event in the Magic multiverse that I will not describe here. Concerning Lorwyn and Shadowmoor the fact that it happened should be enough.

Due to the dualistic nature of the setting, almost everything in Lorwyn has its darker counterpart in Shadowmoor. Lorwyn is a cozy rural fairy tale fantasy inspired by the British Isle folklore. The sun always shines there and even the storms are a made of light instead of pouring rain.

Shadowmoor is the opposite, it is always dark and hostile. It still retains the fairy tale tone, but warm and cozy is replaced with harsh and gloomy. The denizens of Shadowmoor are mostly bereft of their good sides, with their flaws amplified.

The duality of the plane is best seen when the change is part of the equation. Without the Great Aurora the plane is either an idyllic rural haven, or a folk horror darkland. Both have their merits, but a large part of the potential is lost when only one aspect is experienced.

Cosmology

What I am quite interested in is the way Wizards will handle the plane in relation to D&D cosmology. Both multiverses feature planes, but they are not connected.

MtG Multiverse

Based on the Planeshift series my guess is there will be no overlap with Lorwyn either. Rules will be given for playing D&D set in the plane, but you will be expected to act within the MtG multiverse. That’s fine in my book, it makes more sense to travel from Lorwyn to Innistrad, than jump between Lorwyn and Sigil, or one of the many worlds of the Prime Material plane.

In the Magic multiverse one thing you have to consider is that travel between the planes is not easy. Usually the power called “planeswalker’s spark” is required, and the individuals in possession of the spark are known as “planeswalkers”. It takes time and effort to master the spark, so the planeswalkers that could travel to Lorwyn should be fairly high-level.

This changes after another large event in the MtG universe, the Phyrexian Invasion of the Multiverse. One of the the results is that many planeswalkers lost their planeswalking powers. Instead, newly created portals called “omenpaths” now exist, enabling even non-planeswalkers to travel from plane to plane. So the accessibility of interplanar travel depends on your timeline, but more on that later.

D&D Multiverse

Suppose you only wanted to use Lorwyn-Shadowmoor in your campaign. You are using the “default” D&D cosmology, also known as the Great Wheel. From the outside in there are several layers of planes. The Positive and Negative planes are the outermost, then there’s the Astral plane wrapped around the Outer planes, with all the alignment-based fun stuff.

The Inner planes are encased in the Elemental chaos, then there’s the Ethereal plane, and nestled safely in the middle is the (Prime) Material plane. That’s where most of the adventures usually happen, whether it’s on Toril, Krynn, Greyhawk or what have you. Somewhere near the Prime there are the Feywild and Shadowfell, and those are the ones whose relation to Lorwyn-Shadowmoor would need to be resolved.

Personally I would handle Lorwyn as a crystal sphere similar to Realmspace, or Greyspace. One heavily influenced by Feywild in the past, but perhaps cut off since then. Maybe Oona, the queen of fairies is the culprit, seeking dominion and independence in her own plane without intervention from home. That would explain both the influence and isolation, and go well with Oona’s theme of manipulative schemer. But all this depends on another detail of the D&D adaptation, and that is the timeline.

Timeline

The aspect of the plane would dictate much of the tone and play style of any prospective game. There’s actually quite a lot of possible scenarios depending on the timeline the creative team chooses. I believe it makes most sense to present readers with all of the options. They’re making a setting supplement, not a short zine, so there should be plenty of space for that. Everything depends on whether they want to set a particular scenario forth as “canon for D&D play”, or whether they want to give as much freedom as possible.

Before the blocks

The earliest and possibly largest period imaginable would be the one before the Lorwyn block. A time when the aspects were being flipped every couple of centuries by queen Oona and nothing out of the ordinary happened. Or did it?

Prequels are often used and abused by creators to fluff out already established franchises. When done right it can add depth and explain some things that were left unexplained in the original story. When overdone it can lead to the past being more crowded than the main story, and that is not always desirable.

In this scenario we would find some of the more long-lived characters from the blocks, but there would also be plenty of space for new ones. It would give the creators a lot of freedom, and they have the luxury of the Great Aurora effectively resetting almost everything. That gives a lot of leeway for even quite deep plots as long as it’s something Oona can kill with the Aurora.

Lorwyn block

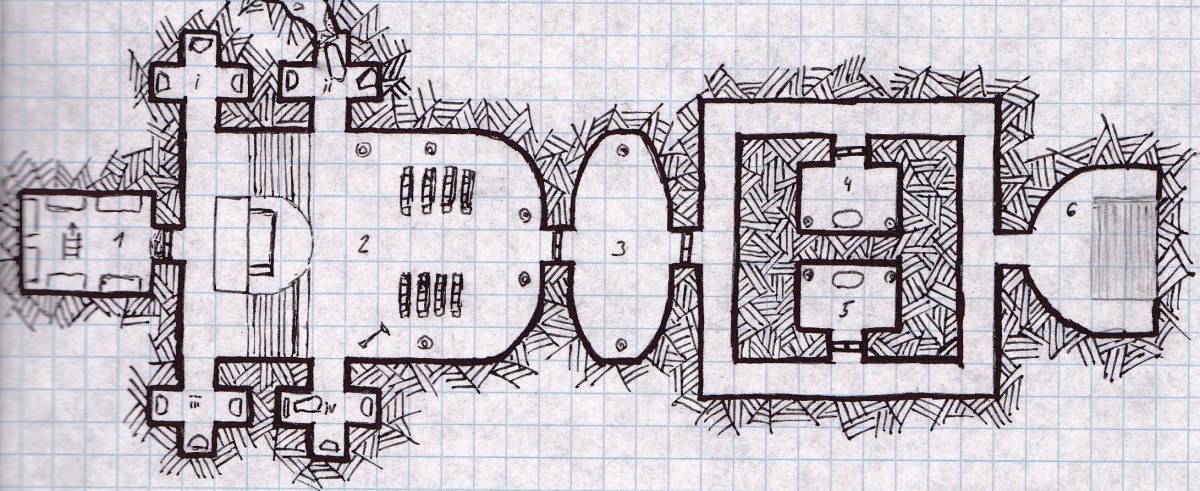

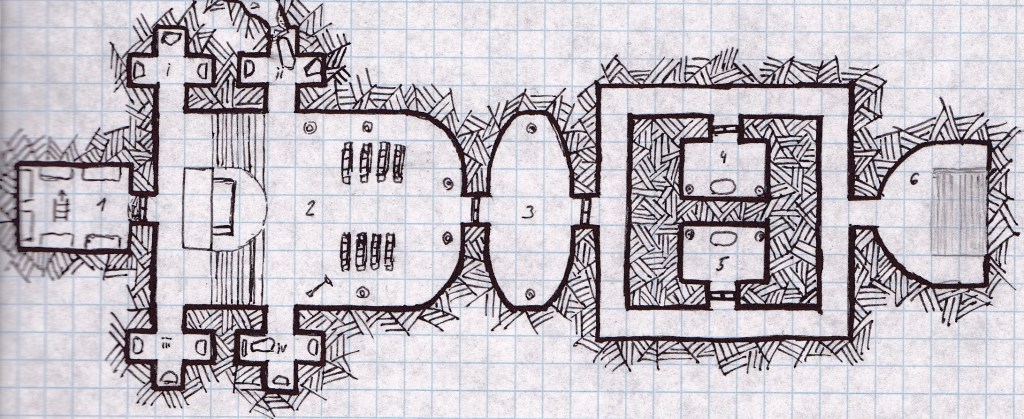

The first two sets of the Lorwyn-Shadowmoor cycle are Lorwyn and Morningtide. The plane is in its bright and sunny aspect, and there is an overall playful mood throughout. The elves are the public villains, and Oona and her fairies the villains in the shadows.

I will not recount the whole story here, you can read it on the MTG Wiki if you like. Just a few remarks. Since there already is a “main story” for the Lorwyn block, there remains less of the freedom for the team working on the new D&D book.

It’s not easy to fit new stories alongside a strong existing main story. In Star Wars such things are possible thanks to the breadth of the universe. In Harry Potter or Lord of the Rings this would be more difficult. In the case of the latter there’s an amazing achievement in the form of the War in the North video game, but such feats are rare.

Shadowmoor block

Shadowmoor was introduced in the eponymous set along with Eventide. The plane has now been shifted by the Great Aurora, and it’s not for the better. Not only almost everyone lost their memories and their good sides. Oona herself is perplexed by the Aurora, as this one wasn’t her doing. In the end Oona’s chokehold on the plane was broken and a new era begins.

A lot of what was applicable to the Lorwyn block story is the same with the Shadowmoor block. There is a story and it might be difficult to squeeze in other worthwhile content without it coming off as secondary. But it can be managed and surely some groups would be able to pull off a nice campaign.

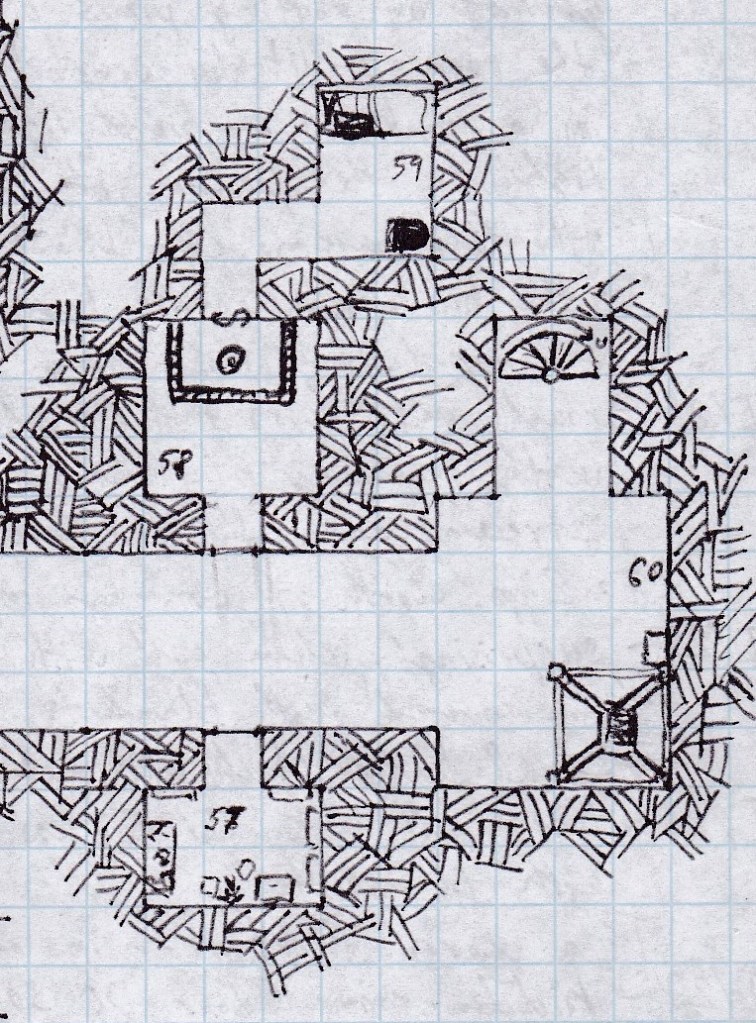

post-Shadowmoor / pre-Phyrexia

The events of the Shadowmoor block leave the plane in a new state, without the constant shifts of aspect. There are no more Great Auroras and a normal daily cycle is restored. The plane should be more or less in its Lorwyn aspect with a few remnants of Shadowmoor. That sounds like a fun mix that’s not all gloomy but still has some darker elements.

After the events of Shadowmoor and Eventide Oona has been dethroned and supplanted by Maralen, though still alive. The elf Maralen is now queen of the fairies and supposedly is going to rule differently. The fairies will probably remain mostly as they were, but we can presume the other tribes will exist in both aspects in this scenario. So we get both kind and xenophobic kithkin, playful and monstrous boggarts, despotic and virtuous elves. The extra Shadowmoor smaller tribes might also stay. It could really mean many cool options for your tabletop campaign.

If there’s only one “canon” scenario, this one would make the most sense to me. Being a sequel there’s a lot to go forth from, and no danger of retroactively stripping logic from already published materials. The only established event concerning the plane of Lorwyn is the one in the next paragraph, and that one should not cause any problems.

Phyrexian invasion

Phyrexia is MtG’s version of hell, a world of machine-and-flesh monstrosities lusting for the whole multiverse to devour and turn, or “compleat” in their own wording. There was an original Phyrexia in the older blocks, that was defeated, but not wholly eradicated. It took hold of Mirrodin (another great plane with a bunch of blocks and lots of great ideas) and transformed it into New Phyrexia, unleashing an invasion into every plane in the multiverse.

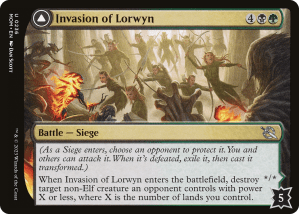

Lorwyn was not an exception, though the focus of the whole story arc was on other, more prominent planes. Lorwyn received only some fleeting mentions. Such is the fate of planes fifteen years dead to the franchise (at the time of Phyrexia: All Will Be One).

The few bits of information that we have tell us that Lorwyn was indeed invaded. There were those who fell to the lure of the Phyrexians, as we can see on the card above. Ultimately the tribes of the plane joined forces to fight back and resist the machine would-be-overlords. The invasion card art shows only elves, but we can see kithkin and presumably others joining in as well, including the wildlife.

The invasion of Lorwyn by the Phyrexians is another scenario well-suited for your D&D game. A whole campaign could be devised, starting with some early pre-invasion reconnaissance being responsible for trouble on the plane. Followed by full-scale invasion, during which perhaps the party would have some vital quest to help turn the tide. The possibilities here are again quite broad, both for the creative team and for the players.

post-invasion

After the invasion most of the planes invaded were destroyed to various extents. We know nothing of the casualties Lorwyn suffered, but since the Lorwyn invasion wasn’t mentioned too much, we could expect a fairly good result. Maybe we’ll get more information in the prepared supplement. It’s also a direction in which a lot of creative work could be done.

There is an opportunity to come up with some interesting worldbuilding, but it seems wasteful to me to set your game after the invasion. Sure, the rebuilding also has its charm, but from a D&D point of view, the Phyrexian invasion is something you want to be part of, when you’re not setting up your game in Lorwyn’s past.

One outcome of the Phyrexian defeat should be pointed out, however. During what’s called the “Desparking” many Planeswalkers lost their spark. At the same time omenpaths have opened, essentially the means of interplanar travel for non-planeswalkers. This opens the possibilities for parties of non-planeswalkers to visit Lorwyn. For example start playing on Zendikar and then travel to Lorwyn. Again, this is something that broadens your options significantly, but comes only after New Phyrexia is dealt with.

Conclusion

Well, the conclusion is obviously that it’s great Wizards are working on a Lorwyn-Shadowmoor supplement for Dungeons and Dragons. The plane has been neglected for too long, and making it available also for people like me, who are more into TTRPGs than TCGs, is a nice gesture.

I posited various questions and their possible solutions for the future supplement. It will be to interesting to see how the team handles them, or even if they do. Maybe what I’m considering isn’t really what’s important here?

Let me know in the comments what are your thoughts, and how would you handle the issues of possible scenarios and cosmology. Also, it’s entirely possible I’ve got some things wrong, as I’m by no means a MtG buff. Corrections are welcome, as well as suggestions, and any constructive discussion. What are your thoughts on the matters I described?

If you liked the article, your comments and sharing would mean a lot, and give me the necessary feedback. The article is quite long, at roughly 12 minutes reading time. Would you prefer articles of this length, or should I strive for more shorter ones in the future?

Last but not least, some disclaimers: Magic: the Gathering (and Dungeons & Dragons, for that matter) are property of the Wizards of the Coast. The cards embedded in the article are obtained via Scryfall with no foul intent. The content of this article benefits a great deal from the MTG Wiki. I am not affiliated with any of the above mentioned entities in any way.