Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

This post is part of a series analysing several aspects of one of the recognizable parts of the TTRPGs we all love – the dungeons. The posts can be read in any order and they will be cross-linked when necessary. Throughout the series (and also elsewhere) “dungeon” is used as a technical term and can be used to describe any clearly defined environment containing multiple non-random encounters. These include natural caves, mines, keeps and castles, crypts, temples, ships and other vehicles, and many others.

This part will be about a concept that lends depth, complexity, and also integrity to your dungeon designs. What is a Palimpsest Dungeon, why make one, and what can it offer? How to make one, even? All this and more can be found below.

Palimpsest

One idea I strongly encourage is “palimpsest dungeon”. This paraphrase of the “palimpsest landscape” concept from historical geography or landscape archaeology seems perfect for creating interesting multi-layered dungeons that make sense. A “palimpsest” is a manuscript that had it’s original writing removed by scraping or washing and then overwritten with new text. Remains of the original text can be sometimes deciphered either by eye or by using modern recovery methods.

In landscape archaeology landscapes are viewed as results of successive actions by humans that have shaped the land. These activities include agriculture, construction, warfare, funerary and religious practices, and resource exploitation. Sometimes the old is removed, sometimes reused in a different way. This may be conscious and deliberate, or accidental.

A good example of palimpsest landscape would be a great barrow, where a warlord’s remains are interred. Rites are conducted on the site for a few generations. A thousand years later the warlord is long forgotten, and the local ruling class starts burying their dead around the barrow. Though of a different religion, they raise a shrine on top of the barrow and observe their own traditions there. After a generation the land is conquered and the conquerors strive to replace the religion present in the region. They remove the shrine and build their own on top of the barrow. After some events it becomes a site of pilgrimage, and a small temple complex is built surrounding the barrow. During construction some of the graves are unearthed and removed, but those untouched by foundation ditches remain. Eventually the site becomes abandoned, its purpose forgotten. New settlers come into the region and a small hamlet sprouts around the windmill built on a convenient mound.

Researchers “read” the landscape from the present backwards. Same as would a visiting party if they arrived in the hamlet described above. You on the other hand have to go from the beginning, setting the layers upon each other as you would a layer cake. With parts of layers missing, pockets of different stuff, and strange combinations. While you better not serve a cake like that to your birthday guests, your party should find it much more intriguing than a 20-centimeter high corpus of sponge.

Palimpsest dungeon

The same principle can (and should) be applied to dungeons. The “typical dungeon”, a complex of underground rooms and corridors, usually isn’t encountered in its original state. The mines were abandoned and overrun with monsters, goblinoids conquered the dwarven city, the once peaceful crypt has been taken over by a necromancer, etc. The layer encountered by the PCs is at least the second one, if not third or fourth. Even in a functioning dwarven underground city there might be parts that lay on top of older layers – old mine tunnels reused as fungus plantations, in turn overrun by mushroom-loving lizardmen.

Having more layers gives you depth on one hand, enabling more complex backstories, but also more options regarding the exploration of the dungeon. Old unused passages might offer shortcuts if found, burrowing monsters might create connections where there were none. Ancient temple underneath a crypt/monster lair/mine is an often used trope. And it makes sense.

Places are often settlet or used for a reason (no surprise there). That reason often stays valid for centuries, whether it’s military importance, environmental features, logistics, or anything cultural. On the surface, when we’re talking landscape, it’s obvious – hills, natural harbours, fertile fields, all these make sure a location will be settled again and again. With dungeons it’s similar. Natural caves will have their climate and water systems that make some areas more hospitable than others. Artificial dungeons were dug out and built with a specific purpose in mind, and this can be seen also by later inhabitants, even if used differently. Prison cells are effectively bedrooms, just not very comfortable. With some work a prison block can be used for living, especially if the beings living there are not too picky.

You might have already guessed that by creating all these layers you are in effect creating a series of dungeons with a common framework, but different contents. Not only it’s a fun exercise, you can also use these in different campaigns or with different groups.

Before you start making a palimpsest dungeon you probably have a few layers in your mind, possibly the latest one and the first one, or the most significant one. For a castle ruin it would be the present ruined state and the most interesting phase of its occupation, though there might be many different phases you want to take into account. Next you want to ask yourself questions such as “What happened between this and this?” or “How did it come to this?”, “What preceded this?”. During this process you might come up with further events leading to more layers.

Or not, not every dungeon needs to be multi-layered. Some dungeons in the sense of this article series aren’t meant to be palimpsests. You could treat a spaceship, or even a seafaring ship as a dungeon, and it would probably have just a single layer. Unless we’re discussing some kind of generation ship, or the Ship of Theseus. A tomb that’s been sealed since the burial also needn’t have more layers. It could be untouched by robbers, monsters, or anything else. The important thing to keep in mind is, as always, logic and consistency.

Keeping track

When designing a palimpsest dungeon it’s easy to lose yourself in all the layers. Especially in more complex and expansive dungeons it wouldn’t do to just note somewhere what the two or three layers are – you might have tens of layers, some only present in one room, others common for the entire dungeon.

One way of keeping track is by labeling layers with a numerical code and making diagrams when necessary. You can find inspiration in the Harris matrix archaeologists use when describing contexts. Do you need to? Absolutely not, particularly not when you’re just preparing a one-shot dungeon for the Friday session with your friends. You might consider using stuff like this if you’re going to publish the dungeon, or if the dungeon is going to appear more than once in different scenarios.

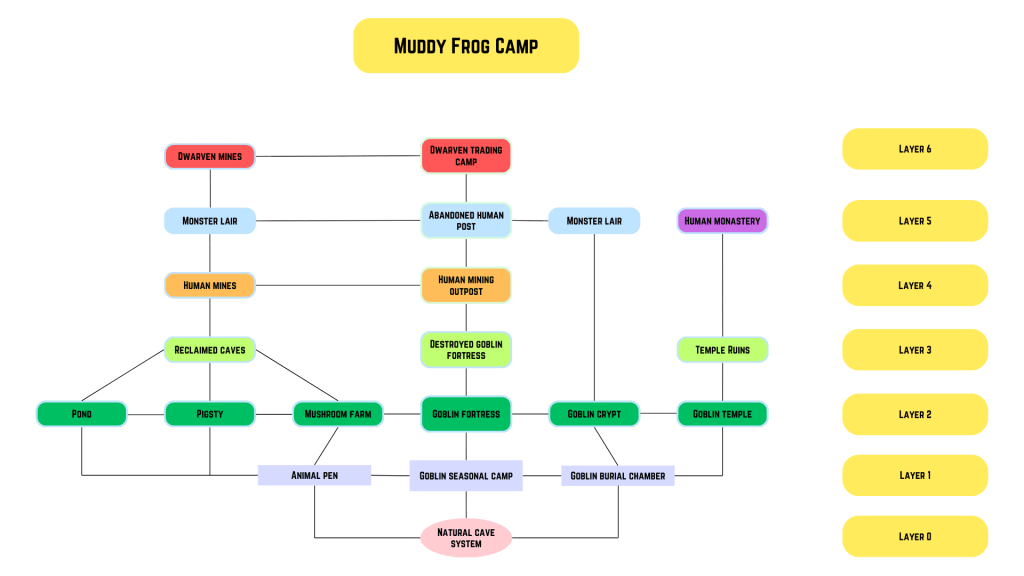

Above is the matrix for a functioning dwarven settlement. Read from the bottom it shows the history of the site in chronological order. From top to bottom the order in which the party might uncover the past is shown. A more detailed overview will have its own article. Right now I can see that when creating the mine section of Muddy Frog Camp, I can use different layers from its past to flesh it out and create interesting encounters and environs. Traces of human mining activities, monster and animal bones, remains of animal enclosures. Creating the matrix (and past of the site) didn’t take that much time, but you can probably see the benefits already. The layers do not represent fixed time periods, one might span five centuries while another merely a few years. Some might also be invisible in the record, for example the mushroom farm or pond in our example, while others might leave a lasting and very clearly distinguished. The more permanent built-up areas such as the temple or goblin fortress are an example of lasting marks.

It is also possible to create a room by room matrix, and depending on the size of your dungeon, it might be a really extensive task. Again, if you’re going to publish your work, or reuse the dungeon in different phases of the campaign or different campaigns, it might be worth the time and effort. Otherwise the dungeon matrix above should be more than enough to help you create and keep track of your dungeon.

Conclusion

Palimpsest dungeon is a concept based on palimpsest landscape. Both describe the results of different consecutive periods of activity in an area, that build upon and sometimes replace the past activities. This creates a multi-layered environment that has depth, consistency, and a logical structure. The layers might be easily readable or only faintly detectable, both cases being useful for creating history and narrative.

To help with keeping track a “dungeon matrix” is proposed – essentially a diagram showing the layers of the palimpsest dungeon and its key characteristics. It is also possible to make a more detailed room-scaled matrix, but in many cases this leads to diminishing returns, as the amount of time and effort required would be inadequate to the benefits.

The terms “dungeon palimpsest” and “dungeon matrix” will be used on this site in future posts, so I hope you paid attention and that the explanations were sufficient. A post dedicated to the model Muddy Frog Camp is on the way, in which I will try to provide a more detailed overview of the whole process of planning, designing, and recording of the dungeon. Hopefully you found this article stimulating, I will be glad for any comments here in the comment section, or wherever you saw this shared. As always, thank you for reading, and if you liked the article, please share it on your social media!