Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

This post is part of a series analysing several aspects of one of the recognizable parts of the TTRPGs we all love – the dungeons. The posts can be read in any order and they will be cross-linked when necessary. Throughout the series (and also elsewhere) “dungeon” is used as a technical term and can be used to describe any clearly defined environment containing multiple non-random encounters. These include natural caves, mines, keeps and castles, crypts, temples, ships and other vehicles, and many others.

This part will be about dungeon size. Why does it matter, what should it be based on, and what other aspects of gameplay should be based on it. And of course I will mention megadungeons as well.

Dungeon scale

How large should a dungeon be? Obviously that should correspond with the needs of your story and plot, but let’s say you have that figured already. Then the size depends on the dungeon – a small local monastery will be different from a regional centre of an order, as will an emperor’s tomb differ from that of a struggling merchant. Some places should be smaller than people expect, while others are often imagined too simplistically.

Often used as dungeons are various underground settlements, whether it’s a dwarven delve, or a goblinoid den. The space required would depend on the social structure of the inhabitants, and the range and scope of activities present. Though it is by no means a rule, more (economically) complex societies usually take up more space. In less complex societies there might be little to no distinction between communal areas, food preparation areas, work areas, and sleeping quarters. Your primitive goblins might occupy a couple of natural caves with only one of them different from the others, taken by their leader. In contrast a dwarven delve would have many separate sections with different purposes, and you probably wouldn’t find a craftsman preparing food in the same room he works in. Even a workshop could have multiple rooms or even levels, and of course housing could range from Spartan-style cubicles to lavish many-roomed residences. Fifty goblins might take up three to four caves, while fifty dwarves might use three to four rooms per unit just as housing (family or individual). Best keep that in mind when designing settlements.

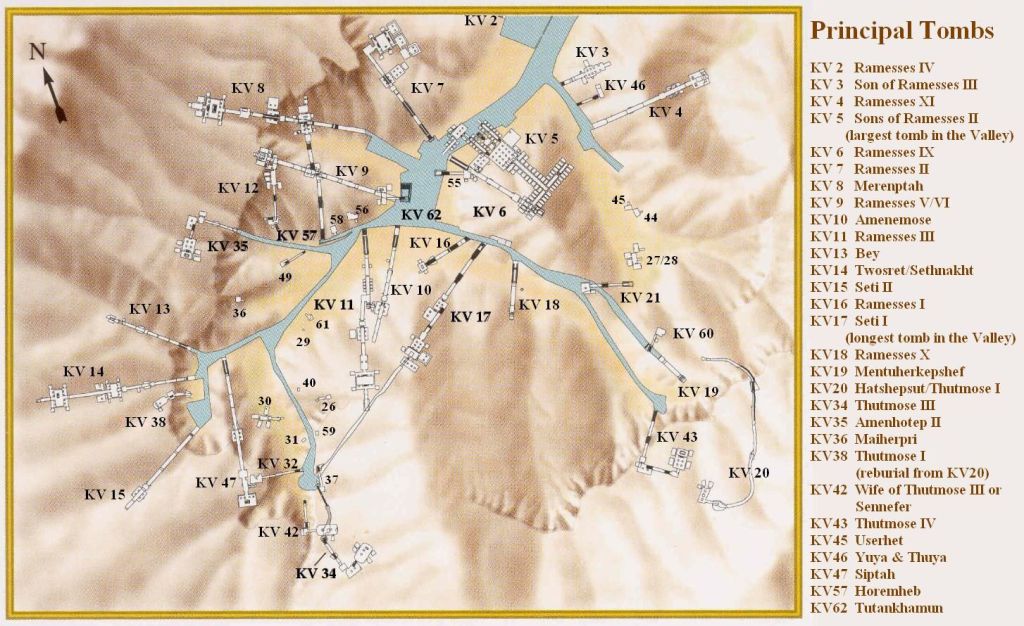

What about tombs? It really depends on their purpose, among other things. When a tomb serves only to inter the remains of a deceased person, you don’t need a lot of rooms – maybe one burial chamber and some room(s) for burial goods, even though these can take up a lot of space in some cases. It is different if the tomb is a place where rituals are still performed – the number of rooms can grow if you have to accomodate the living as well as the dead. Below is a map of the Valley of Kings, where you can see the plans of each tomb. A more detailed interactive version can be found on this great site.

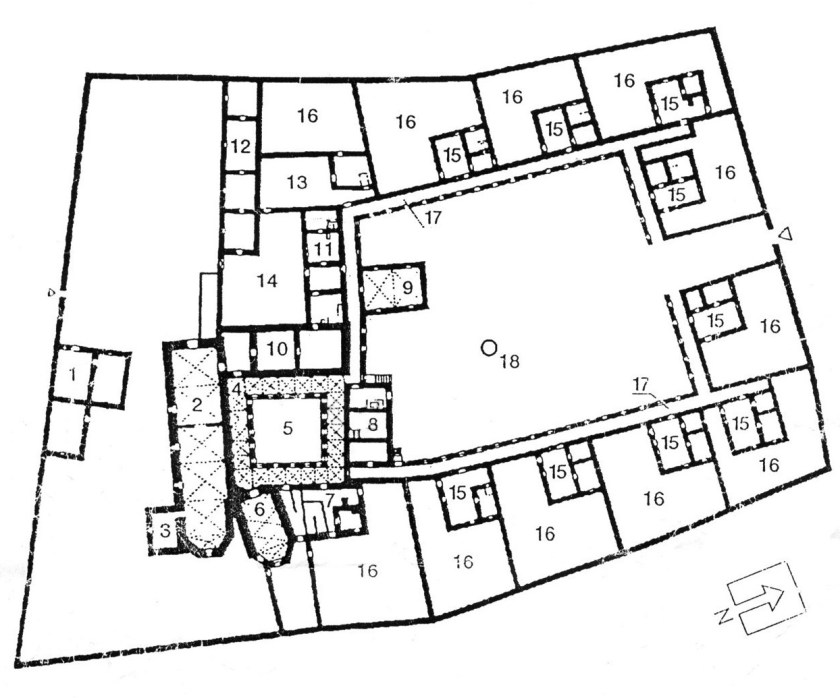

With this we get to temples and shrines. Again a temple needn’t consist of a great number of rooms. A main room (think nave in churches, or naos in Ancient Greek temples) is quite enough for many forms of worship. Often some additional rooms such as a shrine or sacristy will be present. If the temple is part of a monastery, the room count will be significantly higher – a monastery for 15 monks can easily have around 70 rooms, including spaces like gardens.

Room categories

Let’s say you make a dungeon with 20 rooms and only three are vital to the quest, and maybe another five you can imagine as optional. In a very simplified treasure hunt the three would be the key room, the guard room and the treasure room. You have to get the key, then defeat the guard and then take the treasure. Along the way you would find optional rewards or encounters. But there should be more rooms than those, simply because that’s how it would be. In a castle there would be living quarters, kitchens, dining rooms, bathrooms, armories, storerooms, music rooms, libraries and studies, workshops, and a whole lot more that needn’t be part of the quest. But they of course could be. An enemy from an important room might flee to an originally unimportant one, but now the bathroom has purpose as well. More rooms also means more potential for exploration, which some players might find more interesting than encounters.

It surely is a lot of work and it might seem like a waste of time if you don’t even plan on the party visiting the extra rooms. But like in the #Dungeon23 and #Dungeon24 challenges, rooms don’t have to be described with twenty sentences each. Simple “pantry” or “servant bedroom, empty” will do, and you can always come up with something should the need arise. If the room wasn’t important in the first place, you needn’t make it too much detailed all of a sudden. Random charts and generators could help, but they make things, unexpectedly, random. So not for everyone and every setting.

When preparing a dungeon it is wise to note which rooms will be essential (main quest), which will be optional (side quests or bonus loot, lore, etc.), and which rooms are there because it makes sense, but they don’t have much to do with your adventure.

Room effectivity

Sometimes five well-crafted rooms offer more than three dozen dull ones. The amount of time the party spends on one room will of course vary. We can call this “room effectivity”. The important thing is to focus on productive time, i.e. time spent progressing with the plot, learning about the world, obtaining gear or resources. Not all combat encounters are productive, although they certainly can increase the time spent in a room.

Non-combat encounters increase room effectivity nicely. A prisoner in a cell, or a hermit angling for blind fish in an underground lake might offer clues, sidequests, or at least a nice change of pace from exploration. They can be revisited to fulfill some errand received (getting keys for the prisoner). Or the NPC encountered might have answers to something found further in the dungeon. The hermit might know a lot about his surroundings, even if he keeps to the lake. He might even know about another way into the underground city, now that the main tunnel is blocked.

Puzzles also count. We can divide them into two main groups – environmental puzzles, and designed puzzles. I will dedicate another article to puzzles entirely, so here I will just say that by designed puzzles you can understand various mechanisms that have to be overcome for something to happen – these often don’t make sense in a dungeon. The environmental variety is created by circumstances and environment. When the drawbridge is broken the party needs to find another way across the chasm, perhaps using stuff found around. Both varieties increase room effectivity and therefore the time spent in the dungeon.

Megadungeons

One of the issues I’d like to address, especially since this series of articles is based around the challenge aiming to create a megadungeon (see Dungeon 24). Megadungeon is a concept that promises sessions upon sessions of exploration and encounters. It’s one thing to create room after room, level after level, filled with whatever seems interesting at the moment, and another thing for the whole to make sense. What’s the relation between levels 2 and 10? How do they (that is, their inhabitants) interact? Why are there 12 (or 50) levels, anyway? Why is there an elven tomb sandwiched between an orc fortress and dwarven mine?

Settlements can easily give you a lot of rooms – a small community of intelligent beings can occupy hundreds of rooms. I suggested earlier that structures with lots of similar rooms such as settlements, necropolises, or prisons, are good as a backbone for your megadungeon. Be careful not to overdo it by making the whole dungeon one large prison with hundreds of similar cells, or a large dormitory with copy-paste rooms. First of all keep in mind that even such places needn’t be completely uniform in their design, even if only thanks to time and use. Misuse, decay, and damage can also bring variety to an otherwise repetitive spaces.

One thing that makes megadungeons believable, interesting, and less randomly put together is a concept I’m borrowing (and reverse-engineering) from landscape history researchers, such as landscape archaeologists and historical geographers. I call it “Palimpsest Dungeon” and there will be a whole article dedicated to this, so I will keep it rather short here.

The core principle is that a Palimpsest Dungeon has multiple succesive layers (not levels!) that overlap. Each one can change the one(s) below in its entirety or just partially, and new qualities can emerge from the interactions of these layers. This way you can get a dungeon that is ancient, extensive, and full of things to explore without it looking like you just wanted to create a massive dungeon.

Conclusion

Regarding dungeon size first and foremost think how large it should be while still making sense. Don’t create temples that have hundreds of rooms just because you want the dungeon to last a few sessions. Either use sensible sized dungeons (whether it’s a tomb, temple, mine, whatever) and maybe make the exploration and encounter parts more complex. Use non-combate encounters and puzzles to make the dungeon last longer. Or create a Palimpsest Dungeon with multiple overlapping layers, if you absolutely need to have 18 levels and 486 rooms.

What’s your take on Dungeon Size? Do you prefer sensible dungeons, or just want lots of rooms to explore and defile? Are you perhaps one of those rare characters who strive to create expansive dungeons that make sense? Leave a comment and share with your friends!